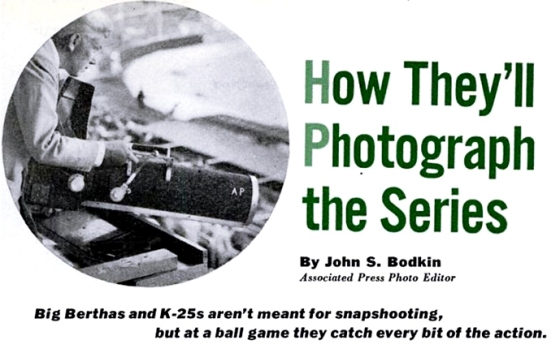

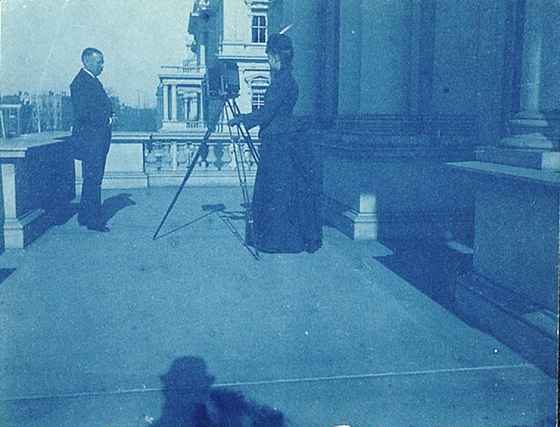

In 1917 The Amateur Photographer’s Weekly published a short piece (it looks like it was essentially a press release) in one of their issues calling on American photographers to do their duty and sell their foreign lenses to the government for use in the war effort. I had certainly never heard of this aspect of WWI, but it makes sense, given that, as the article points out, German lenses were no longer available to be bought in the open market, and they of course made many of the premier lenses of the time. (Great Britain had had to make a similar plea to the public at an earlier point, but by 1917 had managed to increase domestic production to meet their requirements.) The need was for lenses of longer focal lengths (from 8 1/4″ to 24″), for the ”fleet of observation airplanes” that were then being readied. These lenses tended to be “in the hands of professional, commercial and portrait photographers, who are reluctant to give them up,” the piece points out, but “these photographers must be brought to realize that their Government should not be handicapped by them, and it is their patriotic duty to offer their lenses for use.” It goes on to say that there are many other suitable lenses for that sort of commercial work, and that “this fact has been proven beyond a doubt by photographers of great renown who have sold their lenses to the Government.”

Kind of a fascinating footnote to WWI, and it also makes one wonder how many magnificent lenses must have been forever lost that would otherwise have remained safely housed in portrait studios and homes, etc. On a page devoted to “the war in the air,” this WWI site points out that “Reconnaissance missions were dangerous. They were usually carried out by a crew of two. The pilot was required to fly straight and level to allow the observer to take a series of overlapping photographs. There was no better target for anti-aircraft guns, no easier prey for stalking fighters….The twin duties of artillery observation and reconnaissance remained the most important utilization of aircraft throughout the war. The number of sorties flown on these missions far outweighed the number of missions flown on all other missions combined. It was more important, if less romantic, for a fighter pilot to shoot down an observation plane than to shoot down another fighter.”

The above passage is talking about observation aircraft active in the war in general, not just on the part of the Unites States, and when you consider the number of countries involved and the greater length of time others were involved in the conflict, it really makes one think that the combined loss of lenses during the war must have been significant. I have no idea, of course — it would be interesting to see if anyone does — if in the end more were lost than the number that were manufactured (and survived) that would otherwise never have existed had it not been for the increased production the war prompted. Perhaps the relative rarity and expense of vintage lenses of longer focal lengths (widely coveted today by large format and wet-plate portrait photographers) owes at least something to WWI, and to campaigns like this. Or maybe the war actually drove up production to the point that afterwards there were a greater number in existence — though even if that were the case, many unique and valuable lenses (and certainly many that were made earlier) would still have been sacrificed. It is also, I think, odd to ponder the prospect of a piece of glass that 6 months earlier may have been focusing an image of, say, a child in some Main Street portrait studio being blown to bits in the skies over northern France or Flanders. Here is the piece (click to open in its own window/enlarge).